Sewers and the stench meter, or Journey to the bowels of Prague - Novinky.cz<

Sewers and the Stinometer, or Journey to the Bowels of Prague

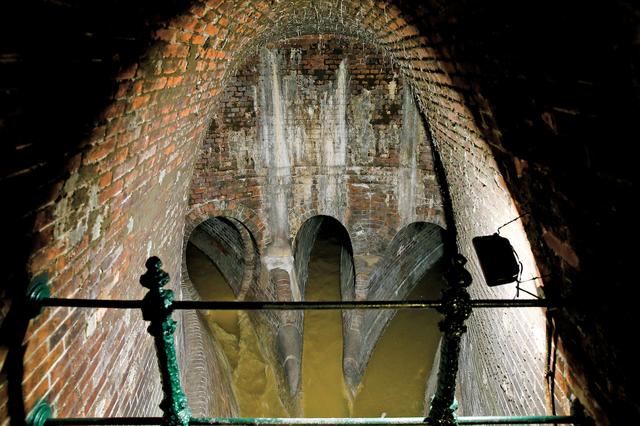

Deep under the Prague streets, far from our pampered noses, more than four and a half thousand kilometers of canals crisscross Prague. Their heart is an original network of canals of strange, gloomy beauty, built at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. In its time, it belonged to the absolute cutting edge of technology and is still functional today, even after a hundred years.

We went down to it (the report was made even before the corona crisis - editor's note) with Jan Bernát, head of the Prague Waterworks and Sewerage (PVK) sewage network survey department, and PVK press spokesman Tomáš Mrázek. First up was the oldest trunk sewer, which is marked A. It starts under the tower of the Old Town Hall and the entrance to it is called Cizinecký: this is where the Prague councilors used to take foreign delegations to show off the modern waste system.

Our guides from PVK unlock the door at the foot of the tower, we take our helmets and go down the stairs to the connecting chamber, in which three collection channels flow: from Celetná, Melantrichová and Železná streets. We're standing right next to the canal, smelly greenish sewage rolling in at our feet. "Be careful not to fall there," warns Jan Bernát. "It's not very deep, but the bottom is slippery. A strong current would trip your legs and you would end up in the sewage treatment plant in Bubenč."

In addition to suffocation in the canals, there is also a risk of drowning, because they react as insidiously as underground caves when it rains. We'd rather go through town to the next part of the sewer.Underground with a stench meter

Climbing into the canal is not just like that. Due to biological decomposition, methane and hydrogen sulfide can accumulate underground, so there is a risk of explosion or suffocation. But also drowning, because the sewers react as insidiously as underground caves during the rains: just a short downpour and they become a death trap. "Summer storms change the channel from minute to minute, and when a wave is coming against you, you have no chance to escape," points out Jan Bernát.

| When you flush or Where does it float today |

| The current path of wastewater is a testament to engineering ingenuity. How does the system work? Most of the metropolis, especially the center, is connected to a unified sewage system, which drains sewage and rainwater through a single pipe. At the beginning, the flusher pushes the waste through the house connection into the street sewer. This connects to a larger channel, which eventually flows into one of the seven trunk sewers, designated by the letters A, B, C, D, E, F and K. The oldest sewers A (draining the Old Town) and B (draining Karlín and Holešovice) remember still Lindley. The newest sewer K is also the widest: it has a diameter of 3.6 meters and drains more than 60% of the territory of Prague. The main sewers lead the waste water directly to the treatment plant on Císařské ostrov, through which it then returns to the Vltava. |

| And how does the modern Prague sewage system differ from the original one? First of all, the scope and complexity. Today, about 4,693 kilometers of sewers stretch under Prague. The system includes nineteen sluices and 132 relief chambers, which, when the critical inflow is exceeded, move the sediment to the treatment plant, while the cleaner water flows straight into the Vltava. About four thousand liters of wastewater pass through the treatment plant per second. It processes more than 126 million cubic meters of sewage per year. |

| The channels are no longer made of bricks, but of special modern concrete, but they have the same profile as under Lindley. And they still work almost automatically. However, the method of water purification is different. The original mechanical principle was replaced by a mechanical-biological one. And the new cleaning plant under construction will already combine mechanical, chemical and biological cleaning. |

So we go back up to the Old Town Square and head along Pařížská street to the Czech bridge. We cross the Vltava river and another entrance to the sewer welcomes us in the pillar of the bridge under Letná. It is open and guarded by a water truck with two employees. They arrived twenty minutes before us to air out. Here we have to be equipped with a "smellometer", a dangerous gas detector, to enter the mine. And the two PVK men stay upstairs at the entrance. On the one hand, they keep watch so that curious adventure lovers don't get behind us, and on the other hand, they represent an insurance policy in case anything happens below.

Finally, it is ventilated and we go down again. This time to the chamber, at the bottom of which, at a depth of two floors, opens a ghostly passageway, another part of the original sewage system. It consists of two cast-iron pipes with a diameter of one meter and a wall thickness of 2.5 cm, which, based on the principle of connected containers, pump sewage from one bank to the other under the bed of the Vltava.

Shybka is still functional today, only newly lined with laminate so that water from the Vltava does not seep into it. From the shift chamber, the sewer under Letná and Stromovka leads to the wastewater treatment plant on Císařská ostrov. But we won't walk in the sewer. It's so risky that you need an oxygen mask and special clothing with high boots for the bigger ones. And the smaller ones are only monitored by mobile cameras.

The first hundred kilometers

Shybka under the Bohemian Bridge as well as the connecting chamber under the Old Town Square were part of the gravity flushing sewage system, which was designed and also built between 1897 and 1906 by the British engineer William Heerlein Lindley.

He had sewers built with the hydraulically most suitable, ovoid profile, which best handled the impact of the water. As a facing material he chose - and defended it through the lobbying of concrete plants - "obsolete", twice-fired bricks called bells.

They sounded beautiful when tapped, but above all, they resisted moisture and pressure very well. They were custom-made for the new canals and were brought to the construction site in wagons lined with straw so that they would not be damaged.

The new network consisted of more than a hundred kilometers of canals covered by a barrel vault, and the entire system opened underground into the original Old Wastewater Treatment Plant in Bubenč, which now serves as a cultural center. We go there to meet Šárka Jiroušková, the press spokesperson of the Továrna company, which manages the unique monument.

The old treatment plant was built between 1901 and 1906 as the last link in Lindley's sewer network. It served in continuous operation until 1967, when it was replaced by a modern mechanical-biological treatment plant on the neighboring Císařské ostrov. Our grandfathers nicknamed the dry cleaning plant Podělajn Karlštejn. The epithet referred to an uninviting smelling purpose, the name of the castle then to a unique architectural concept, which it can also boast of. Of course, it is not medieval, but built in the spirit of industrial art nouveau.

Filmmakers love it here. For example, Gerard Depardieu walked through the Prague sewers in the film Les MiserablesThe facade with high arched windows, elegant chimneys and brick vaults in the underground are pleasing to the eye, but the main criterion is respect for the purpose of the building: everything still works today, from electric combs to two steam engines Breitfeld & Daněk from 1903. The old cleaning plant became a national cultural monument in 2010, and this year it is being considered to be added to the list of monuments that the Czech Republic annually nominates for inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List. No wonder the beautiful building attracts filmmakers.

It was used as a backdrop for the production of sixteen films and series. For example, Major Zeman joined the side of the workers in the series Fox Hunt in the yard of the cleaning plant. Gérard Depardieu in the role of Jean Valjean walked through the local sewer in the film Les Miserables. And Tom Cruise abseiled to the drain of the dry cleaners like to the underground of the bank as agent Ethan Hunt in the movie Mission Impossible: Ghost protocol.

Fresh air, clear water

Sárka Jiroušková and I go down the stairs to the largest area of Prague's sewage system, the sand trap in the Old Wastewater Treatment Plant. In contrast to a rapid or a foreigner's entrance, there is clean air and clear water where you can see down to the bottom at a depth of several meters. Prague's waste already flows to the treatment plant on the nearby Císařská ostrov, where the canals bring only rainwater.

Originally, however, three main collecting sewers flowed into this underground reservoir, and the first stage of mechanical sewage treatment took place here. The coarsest dirt, soaked remains of feces, rags, papers, corks, leftover food, pieces of branches, leaves, and sometimes even dead cats were caught on simple grids called combs. Captured rakes were manually removed by the operator with special rakes (electrically powered rakes were used later). They were disinfected with lime and exported to the neighboring Císařský ostrov, where they were used to level the terrain.

A suction pump located in the middle of the trap at the place with the deepest bottom sucked the settled gravel into the sand washer behind the building and after washing it was used as construction material. In the overflow along the edges of the trap, other, this time fine combs that caught fats and other organic impurities filtered the water. Wastewater flowed through them into settling tanks.

There are ten sedimentation (decantation) tanks underground behind the treatment plant building. They are placed parallel to each other towards the river and connected at both ends by through galleries. They have a length of eighty-eight and a depth of up to six meters, and they are made of perfectly jointed masonry.

In operation, the tanks were always in pairs: waste water from the trap flowed into them for several days, then the supply was closed and the water remained stagnant for about a week, so that even the finest sludge had enough time to sink to the bottom. After that, the clean water was drawn to emptying wells and from there pumped through the sewer to the Vltava.

Sediments from the bottom of the decantation tanks were manually raked by the workers into the deepest part of the tank, called the sludge pit, from where the sludge pump drove them further: in the winter for one more thickening into the sludge wells, in the summer straight into the sludge on Císařská ostrov or into the sludge ships. Sludge was taken by farmers as a desired fertilizer. All pumps in the treatment plant (suction, sludge, flood) were driven by two high-pressure steam boilers. They are the only ones of their kind in the Czech Republic that still operate on steam and are still operational today.

"Sewerman" Sobol was calmly pulling out the nylon hose filled with sewage with one hand, while holding bread and snacking with the other...How things went in the sewage treatment plant, the shift foreman of the cleaning units Jiří Fikar and Jan Bartůněk recall in a Czech Radio report. Both worked in Bubenč in the 1960s. "The first impression was shocking. When I went down to the trap, I admired how people could stand the smell," says Jiří Fikar. Men of various professions gathered here: butchers, cobblers, painters, tailors, wintering circus performers, but also released criminals. They were nicknamed "the sewers".

However, not everyone would have the stomach for their work - for example, like the famous Franta Sobol, who took care of the flawless operation of the suction pump in the sand trap: with one hand, he calmly pulled out the silon stockings filled with sewage, which wound up on the impeller, with the other he was holding a slice of bread with salami and snacking…

The worst - but well-paid - jobs then included raking the settling tanks. Three men in tall fishing boots and waterproof trousers climbed down a ladder into the drained tank, waded through the sediments, and side by side, rake by rake, they were scooped into the tailings before them. "The main motive was money," admits Jan Bartůněk.

But money doesn't always come first. Jan Bernát has been working for Prague Waterworks and Sewerage for more than thirty years, and he is proud of it. "I don't hide the fact that I'm a channeler. I have my status honor," he says.

Golden shit!

However, even a modern system solves problems. The most difficult thing for the employees of the Prague Waterworks and Sewerage are the restaurants in the city center, which discharge waste from their operations straight into the canals. Much to the delight of the rats. It is said that there are five of these "cute" rodents per Prague resident...

And what is even worse, restaurants - especially those in the center - but also households often discharge used oils into the canals. These solidify in cold water and, together with sand and paper, form a hard mass that often clogs the channels and thus heats up the surroundings. “The grease is worse than concrete, and it stinks like crazy. Golden shit against it! They have to attack her with pickaxes," complains PVK press spokesman Tomáš Mrázek.

"That's why every municipality is obliged to dispose of used fat from this year. If a special bin is not set up for this, citizens should pour it into a PET bottle and take it to the collection yard. However, from my sewer point of view, I think that they can easily throw the pet with the used oil in the mixed waste. It burns well in the incinerator, and it's still better than if the oil ends up in the canal," concludes Jan Bernát, head of the survey of the Prague sewage network.

Tags:

Tags: Prev

Prev