Two weeks in Armenia: Aragats, Geghard, Sevan, Vardenis<

Preparations for departure to Armenia were in full swing, from the original seven travelers only Bzuk and his friend Petr dropped out, so the final five were Ondra with Lucka and I with Křemílk and Bojínek. We left before ten in the evening, which bothered me a bit, because you can't see much from the plane at night. In the end, we caught a little glimpse and realized that the Black Sea really lives up to its name. We landed in the Armenian capital of Yerevan a little after four local time (i.e. GMT +5 with summer time).

Yerevan doesn't wake up until nine o'clock

Our first concern was getting a visa. This is provided for 21 days at a price of 3000 drams (which is the local currency convertible into the Czech crown at a ratio of roughly 20 drams to 1 crown). However, it was necessary to fill out a form containing such questions as the place of accommodation or a contact in Armenia. Of course, we didn't have that, so the officials didn't want to give us a visa at first - they couldn't understand that we just wanted to walk around the countryside and sleep under a tent. But in the end they made an exception for each of us and we were able to move on.

The way out of the airport was a winding path that subtly led us directly through several shops. There was an information kiosk in the not very large exit hall, but the lady stationed there was probably a summer worker who didn't know anything, she didn't have a map of the city either, and actually only knew the number of one taxi driver. But in the end we got a taxi ourselves - for 1000 drams, he stuffed all five of us and our luggage into the lady and took us to Republic Square. It was about six o'clock and it was just beginning to dawn.

Business activity in Yerevan (and probably in the whole of Armenia) does not start before nine in the morning. That's why we hung out in the park for a few hours and while most of them were sleeping, Křemílk and I went on a light exploration of the surroundings. We needed to buy water and gas cartridges for the stove. According to various sources, an outdoor equipment store was supposed to be located next to the Moscow Theater, but this was not the case. Finally, we tried to find the information center, which in turn was supposed to be located in a street not far from the square. But that is no longer true either, so Ondra and I started to get information from various travel agencies. But if someone understood at all what we actually wanted (staying outdoors is probably not a very widespread activity in Armenia), they had no idea where we could buy something like cartridges.

Most people sent us to some kind of market, where we ended up going. It was quite an interesting market with hardware products, but we couldn't find a gas cartridge here. The last hope was two tips from an English-speaking lady in a travel guide, who sent us to a store similar to our drugstore and to a supposed outdoor shop called Dangerous Height, but it was supposed to be twenty minutes away from the center. We chose a drugstore not far from the mentioned museum and celebrated a partial success - the merchant had gas stoves, but unfortunately he didn't have cartridges for any of our types. In the end, we had to buy a new stove, into which small gas cartridges were inserted. Unfortunately, the stove was very bulky, but it was the only option to cook something outdoors in Armenia. We spent half a day searching, while Ondra and I walked through half the city, which was extremely hot, crowded and dusty. We immediately rejected the original plan to come back here after a week to see him.

Fact window: The capital of Armenia, Yerevan, is not a small city - with its 1.13 million inhabitants, it ranks on the same level as Prague. Its history dates back to the end of the 8th century, when an ancient fortress stood here. However, Yerevan experienced a period of development only in the 20th century thanks to a large wave of Armenians returning to their homeland. Another boom, mainly in the field of construction, was experienced after the collapse of the Soviet Union, especially in the last decade. The city center itself is therefore an example of modern Armenian architecture financed by Russian millionaires. In contrast to this are the side streets and markets that have not yet succumbed to the demolition and construction process.

Yerevan has a metro that is easy to use - passengers buy a card and equip it with the minimum credit needed to ride the subway. If he no longer intends to use the card, he can return it and get back the money he used to buy the card.

The route is a minibus

The second task of the day was to go to a small town called Jehegnazorz. We arrived at the place where, according to the Lonely Planet guide, the buses were supposed to leave. A lot of marshrutkas, which are minibuses that usually leave only when the capacity of about 10 people is full, leave from there, or they function as public transport. We looked for something like a bus stop with a timetable in vain, the marshrutka drivers were also unable to answer us. Finally we were caught by a small metrosexual Armenian who promised to show us where the buses leave from. On the way, he offered to take us to Jehegnazorz in his minibus, which had live Armenian music, if the buses didn't run. We arrived at an empty parking lot, where the Armenian told us that there would be no bus today and if we wanted to go with him. For 3000 drams per person, he would throw us there. But according to the guide, the bus was supposed to cost 1000. We started to argue, part of us wanted, the other part was still looking for buses. In the end, the argument was so long that the little Armenian began to lose his temper.

"So do you want to go to Jehegnazorz or not? It's the same price as the bus!" he persisted, casually calling his driver, whom he showed us. When we still weren't ready to leave, he started chatting with the stallholders standing nearby, eagerly explaining to them that we must have fallen on our heads, if we want to go somewhere, he can take us there, and we can continue to sit on the steps.

"I don't think you want to go to Jehegnazorz at all," he finally revealed our intentions and then went to the parking lot to make a phone call. He yelled into the phone for a while, putting it in front of his face so he could scold him face to face, then returned to the booth and started arguing with the cook. He calmly took him by the neck, pointed a hot grill rake at him and told him to calm down. But we didn't want to wait any longer and went back to the marshrutka departures. After a while, we managed to take one of them to another part of the city, from where marshrutkas left directly to Jehegnazorz for 1200 drams per person.

Crossing the Vardenis mountain range from south to north

The journey took a good two hours, we arrived in Jehegnazorz only in the early evening. From there, two taxis took us to the mountains not far from the Tsakhats kar monastery. I'm surprised that Lada and Passat didn't have a flat tire given the quality of the road we were on. It contained a large number of stones, gullies, steep hills, one ford and, surprise of the world, even a sign about the patronage of a project by the European Union!

The taxi drivers dropped us off at the turn to the monastery. We were finally away from civilization. We went another half kilometer and set up our first camp. A short distance below us was a spring of water, which we used to replenish fluids after proper disinfection. After dinner on the fire, we went to sleep.

We woke up late in the morning, we haven't adjusted the time difference yet. We didn't set off until around ten o'clock, when the sun was already quite high. After a hundred meters, the road branched off to the Smbataberd stronghold, to which only I, Bojínek and Křemílk set out with ease. The fort stands on the spur of the ridge about a kilometer from the turn.

Fact window: The first mention of the Smbataberd fortress dates back to the 5th century, but 400 to 500 years later the fortress was rebuilt and better fortified. The building is strategically located at the end of a ridge rising south from the Vardenis Mountains with a good view of the two neighboring valleys. It is protected on three sides by an impassable slope, it was supplied with water by an underground tunnel leading from the nearby Tsakhats kar monastery. The guard castle is still in excellent condition today with well-preserved extensive fortifications.

After our return, the ascent to the monastery followed. We were starting from an altitude of about 1800 meters and the monastery should have been a good 600 meters higher. The heat was insane, and for the first day with a backpack on my back, it was a pretty decent portion. We reached the monastery around noon - a half-kilometer detour leads to it from the main road.

Fact window: The Tsakhats kar monastery is a tiny building 3.5 km from the Smbataberd fortress. The monastery contains two buildings dated to the end of the 10th century - Surb Hovhannes and Surb Karapet. Around Surb Karapet, you can see a considerable number of relief plates, so-called khatchkars, depicting a cross carried by a sun disk, similar to the well-known Celtic crosses. There is a spring near the monastery, a source used by the fortress of Smbataberd. You can sit by the spring in the shade of an apple tree. As everywhere in Armenia, it is better to disinfect the water first.

We lingered at the monastery for a while, refilled our water and then continued further into the mountains. The path first passed through one village, from which the local shepherds directed us to another, and also the last village in these mountains, at the beginning of which we met an elderly peasant.

"Barevdzes!" we called in Armenian. "Barev," answered the peasant and immediately asked us where we were from. "Czech Republic." The shepherd shrugged. "Czechoslovakia," we specified, and the peasant already knew.

His house was the same as all the others in this village. A low stone hut with a wooden roof overgrown with grass. A cell inside, a woman in a cell. We took a photo with both of them, then the farmer turned on the radio to show that he was no stranger to modern technology and invited us inside. We sat down at a small table, introduced ourselves, which made Rafi and his wife Lida very happy. Lida cut a watermelon and a cucumber for us. In return, we gave them a postcard of Prague and round cookies. We talked for a while about where we were going, how long we would be in the mountains and how cold it was at night.

"It's twenty-five here now, but it's fifteen at night and I don't go out without a winter coat," Rafi insisted. "And how is it here in the winter?" we scouted. "We're not here through the winter. We're only here for five months during the summer and we go down to the city for the winter," Rafi explained.

Vardenis Volcanic Mountains

Then he advised us where to go next to climb up to the Vardenis plateau and we said our goodbyes. The path from his abode led us past an ice-fresh stream and then sideways up the hillside. We climbed to about 2,800 meters above sea level and set up tents.

No sooner had we done this than a herd of cows started coming down the hillside in front of us. We moved the tents a little so that the cows could pass, but they certainly did not choose the path, so we suddenly found ourselves in the middle of the herd. But Bojínek left her backpack on a stone nearby, which the cows couldn't help but notice. They licked the backpack curiously, and Bojínek prayed that they would just stay there. The passage of the herd went well for us, Bojínek only had to wipe the cleat for a while. After sunset it started to get quite cold, so we believed Rafi's claim of fifteen degrees and put on our jackets. But it was still possible to sleep only in underwear.

It was still cold in the morning before sunrise. We managed to start on the ninth, we still climbed about a hundred meters, then it was more or less flat. We started to take the direction to the top of Vardenis. According to our Russian maps from the 1970s, a highway should lead along the ridge. But we found out that what is marked as a path on the map can actually take on up to three forms. Either it is really a dirt road, like the one to the Tsakhats kar monastery, or it is a path that gets lost in places, rather trodden by shepherds and animals. The last variant is an impassable landscape where, even according to the natives, no road has ever existed. Our ridge was mainly the second type of route.

Fact window: Vardenis is of volcanic origin and all the rocks here have sharp edges and are usually slab-shaped. Despite its high altitude, the plain consists mainly of grassy areas, disturbed in places by stone fields. There is certainly no shortage of water - the mountain range is quite rich in springs, although often these are only small trickles.

The peak of Vardenis is the mountain of the same name with an altitude of 3522 m. The summit cap is already a real stone sea, where movement is difficult due to unstable stone slabs. They move easily when walking - thanks to their volcanic origin, they don't have a lot of weight.

We walked past an artificial water course that gave us the persistent feeling that it was flowing uphill. But it was a very successful feeder crossing the landscape along an almost perfect contour. After a while we reached the main ridge, where the plain passed into a wide valley leading to Lake Sevan. Altitude 3300 m a.s.l.

The road turned to the east and the peak of Vardenis could already be seen in the distance. The heavy haze made all distances seem much greater than they actually were. That's why we were always surprised by how quickly we managed to move from point A to point B. But we didn't reach Vardenis that day, we anchored in front of one of the saddles that still separated us from the highest peak. The rain was catching up with us. We still managed to take an evening bath in the stream about 100 meters below where we were lying, but the return to the tents was already in the fog and the beginning of rain.

Sunday morning was sunny again. We packed up and set off to conquer Vardenis. The path first descended along the ridge to some 3100 meters, then the ascent began below the summit. At first, we debated whether to conquer it that day or leave the ascent for the morning. Still undecided, we started to go around the summit from south to east and thus reached relatively high up its slope. Therefore, we decided to make a detour, leave the luggage in place and go to the top. The only problem was visibility, which changed rapidly. When we reached the highest point, a cloud enveloped us. But before long he went away and we had a view not only of the mountain range, but also of Nagorno-Karabakh in Azerbaijan and Lake Sevan in the north. We enjoyed ourselves and then descended back to the road. We camped a little further. Once again we were overtaken by a storm and persistent rain that lasted a good part of the night.

The sun did not disappoint and the morning came out again. A lengthy descent to the shores of Lake Sevan followed. First it was necessary to descend to the bed of the river flowing from the slopes of Vardenis and then along the ridge towards Artsvanist, a tiny town on the coast. We got out of the mountains pretty quickly, but we still had a long way to go to the lake. Now the gravel road stretched across the bed of another watercourse cut in the rock, the final three kilometers to the town were already on broken asphalt.

A dog barked in Artsvanist, only on a larger patch, which could very well have been the main square, several men were standing, one of them leaning on a tree and strikingly resembling Fidel Castro in his appearance. I asked him if there was a taxi to Martuni, where we were headed.

"Taxi?" Fidel asked, pointing his thumb at his car. "Here's a taxi."

We suspected that Armenians consisted only of farmers, soldiers and taxi drivers. We started arguing about the price and agreed on 5000. But since there were more of us, we got into a bigger vehicle – a UAZ driven by one of Fidel's friends – and set off to Martuni. Here we changed to a marshrutka, which took us to the city of Sevan for 1000 drams per head.

From Sevan to Geghard Monastery

On the beach of the Sevan peninsula we started looking for a place to sleep and water. I was hanging out among the Armenians when I heard: "Please, aren't you Czech by any chance?" I looked back and saw among the tanned natives a young lady who clearly did not belong among the others. I answered her in the affirmative, and in return he learned that he and his friend were camping on a hill at the end of the peninsula - they say there is a patch of land behind the Sevanavank monastery where you can spend the night. Then she invited us to the flat, which is how I fulfilled my task of finding roommates. In the evening we went to a hotel under the monastery to try Armenian cuisine.

Fact window: Traditional Armenian snacks are a homemade pancake called lavash, which is served here as a side dish instead of regular bread. In a restaurant, you get lavash already broken and often too thick. Proper lavash is very thin, reminiscent of a Spanish tortilla, but unlike it, it can be half a meter long and no less wide. Among the meat dishes, shashlik is worth trying - usually pieces of lamb skewered on a skewer. A specialty for the brave is hash, which is a leg of sheep or veal cooked with garlic, tripe and herbs. In general, Armenian cuisine is rich in vegetables, but at the same time it is a moderate and undemanding diet suitable for hot days.

After a few Kotayk and Kilikia beers, we went behind the monastery to set up our tents. We also had time, because storm clouds appeared on the lake in the south and the fresh wind drove it uncompromisingly towards us. Surprisingly, nothing came during the night and even the wind died down. We got up early in the morning, we wanted to catch the sunrise. It did come out, but it was covered by clouds that roll over Sevan almost constantly and in a very strange way. As the lake surface is located at an altitude of 1750 m, the rain clouds have their base only a few meters above the surface. When it rains from the clouds, the drops appear to bounce back into the clouds.

Eventually the sun peeked out and we hurried to the beach. But before we got into our swimsuits, the sun was behind the clouds again. Nevertheless, we took a bath, after which a guy came up to us with several of his friends and absolutely wanted to take a picture with us. He probably liked our hardiness, but he promised to send us the photos by email (and he also kept his word).

After the bath, the transfer to the city began. The taxi driver wanted to take us all the way to Yerevan, where we were headed, but we decided on a cheaper marshrutka. The city of Sevan basically consisted of a single main street with several shops, banks and also a minibus stand. From there we got a marshrutka to Yerevan, bought groceries and also tried the local fast-food, which we soon renamed to slow-food. But the kebab and shashlik were worth the wait, and we also had a nice chat with the owner of the snack bar.

We then took the route to the outskirts of Yerevan, where we were immediately picked up by a taxi driver who took us in a single car to Garni, a small town about five kilometers from the Geghard Monastery. He dropped us off next to the ancient temple, where Ondra and Lucka later went to see. We were already quite hungry, so we went to a tavern in the neighborhood of the temple. We sat there so much that we spent the whole afternoon there, which incidentally was helped by the slow and forgetful service. In the evening, we started looking for a taxi to the Geghard Monastery - we asked an old lady who had just said goodbye to her market woman friend for a taxi.

"Do you need a taxi? My husband is a taxi driver," the lady confirmed our theory about the ratio of taxi drivers in the business sphere of Armenia and ran with us to her house, from where individual residents started to come out and look for the taxi driver grandfather. After a while, grandpa actually arrived, loaded us up and drove us to the Geghard monastery. He offered us his other services in the parking lot.

"If you need, I will take you wherever you want." So we told him that we plan to come back to Garni tomorrow and go to Aragac from there.

"Aragac? No problem," Grandpa began. "Come tomorrow, I'll host you - it'll be free, right. And then I'll take you wherever you want. In the city, a taxi costs 100 per kilometer, in the countryside 150. And I'll take you wherever you want for 100. That's convenient. My son also has a taxi, so we will go in two cars."

This could not be opposed. For now, we thanked and said goodbye. Grandfather snorted away with his lada and we entered the monastery after a short paved path.

Fact window: Geghard Monastery [gechard] and the Azat Gorge are part of UNESCO and there is a good reason for that - the monastery is not only a picturesque building, but also very old - the original monastery stood here already in the 3rd century AD and was here according to the story brought one of the thorns from the body of Christ (hence the name of the monastery Geghard, which means a point). The main chapel was built only in 1215. The monastery is very well-preserved for its age, especially if we add to this the erosion processes caused by the water of the local springs. But perhaps it is thanks to the action of the spring that the monastery is in such good condition - it is said that living water springs from the spring. It is said that whoever touches her will stay young longer. The monastery chapel looks like a small, modest building from the outside, the surprise is even greater from the vast interior spaces with stunning acoustics.

Due to its popularity, the monastery is heavily visited by tourists, but it still functions - baptisms, weddings, even ceremonial rituals with animal sacrifices are performed here. The usual dose of souvenirs and refreshments is prepared here for tourists - we discovered another Armenian delicacy here - sweet sausage or casings filled with sweet paste and nuts.

Behind the monastery flowed a river not unlike our Otter. We washed in it and started looking for a place to sleep. But on the patch we liked, we disturbed a couple in a more than intimate sacrifice. Fortunately, Ondra made an arrangement with the local castellan, so we could spend the night directly under the walls of the monastery. An elderly Frenchman joined us for the night and told us about his experiences in the Vardenis Mountains and also how he saw a bear from afar. At night, a storm visited the monastery, as well as several couples in love. But the couple didn't stay long, because it somehow bothered them that in addition to them, we were also at the monastery. The storm rumbled for a while, creating deafening echoes in the gorge, but then it too fell silent.

We set off from the Geghard Monastery in the morning before the crowds of tourists arrived, planning to walk along the river and then climb the slopes of the Gegham Mountains. We still went down to the river easily, but the path that was marked on the map along the river belonged to those that, according to the locals, do not lead here and never did, which a local native confirmed to us with a smile. But since we didn't want to walk back to the road, we decided to walk a bit along the river bed and climb up the slope as soon as possible. After a kilometer or so of rock hopping, it really seemed possible, so we started scrambling up the hillside.

"This is how I imagine an active vacation," Ondra cheered, pushing Lucka in front of him with a hiking stick. At first, a footpath led up, but it quickly got lost in the thorny bushes, which made it difficult for us to go up. After about two hundred meters in height, the bushes finally gave way and only grass and heat remained.

Once we scrambled to the first level, we built a makeshift shade and weathered the midday heat. When it became unbearable even under the celt, we continued on the path that led further up the hill. We originally intended to visit another monastery called Havuts tar, but soon changed our minds and just followed the footpath along the ridge back to Garni. As we scrambled up the ridge, we saw the peak of Ararat in front of us. His white cap peeking out of nowhere above the streak of clouds literally captivated me. Ararat rose from the surrounding plain like an apparition, and for me personally it was the greatest experience of the day.

Fact window: One of Armenia's many national prides is the legendary Mount Ararat. The way Ararat rises above the Armenian highlands explains why the authors of the biblical story of Noah chose it as the destination of his sea voyage. The white cap of the peak glacier rises to an impressive height of 5137 m above sea level, the mountain is of volcanic origin and was an active killer 172 years ago. The main peak has a little brother with only 3896 meters. But Ararat is not on the territory of Armenia - after the genocide of the Turks during the First World War, Armenia lost a significant part of its once large territory, including the beloved Ararat. Nevertheless, even today's Armenians consider the mountain theirs, they have it on the packaging of cognacs, you can find it on almost every postcard, in the names of restaurants, etc.

We spent some time staring at the Turkish 5000 and then began the long descent through arid mountains surprisingly rich in insect life forms. The last stage already led through a sparse forest of thuja, the last meters of the path ended behind a kind of gate. Two Armenians climbed out of the house by the gate and immediately attacked us:

"Where are you coming from?""From Geghard," we answered truthfully, but the guys looked puzzled."Have you been to Havuts tar?" so you can come here."

Now we were looking incomprehendingly again. But one of the guys just waved his hand and sent us away. We turned around in front of the gate and saw the sign Khosrov Forest Reserve on the post. We accidentally entered the national park, where you can only pay a fee.

We still had to descend back to the river and from there up to Garni. We stopped at our familiar taxi driver, his son treated us to homemade lavash, cheese, coffee and excellent homemade mulberry. Then the taxi driver grandfather arrived and we started arguing about the destination and the price. Although he promised to take us anywhere, he didn't want to go to Aragac, because he said he wouldn't go there. But he offered to take us to Ashtarak, a town not far from Aragac. They took my son and me there for the agreed price of fourteen thousand for two cars.

From Ashtarak to Aragats

Grandfather promised us that he knew Ashtarak and that he would take us to a place where tents could be pitched, there was water and it all sounded like a camp, but then he dropped us off at a gap between apartment buildings, where there was only a monument and water was only available in a hose, which was being watered by an Armenian lawn here. He also started talking to us right away, it came out of him that everyone here in the district knows him and if we need anything, he is the right person to turn to. Just a big boss. We bought a watermelon and pitched our tents at the place in the clearing that Armenian had shown us. We were a bit groggy from the night between the flats, but in the end it was one of the most restful nights so far.

In the morning, the Armenian asked us if everything was okay and also advised us where buses and taxis depart from. We bought groceries at the local market and set off to find a taxi to Aragats. The guide announced that you can get there for 3,000, and we read travel books from people who didn't go there at all with Lada or Zaporozhets. That's why we hesitated for a long time before deciding on a pair of pilots - one with a Lada, the other with a Volga. We agreed with them on 5,000 per car, threw our backpacks inside and headed north. There is indeed a bad road to Aragats, but both drivers handled it with flying colors. They drove up to Lake Kari at an altitude of 3190 meters in a manner that indicated that they go there almost every day. They even gave us a phone so we could call them if we wanted a ride down again.

Fact window: Once the Armenians lost Ararat, the Aragats volcano became the highest mountain. Its peak is more than a kilometer lower, but that does not detract from its majesty. On the contrary, with its peak torn to shreds and a crater torn in the middle, Aragats is a true wilderness. The crater is surrounded by four peaks named after the cardinal directions. The northern one is the highest with 4095 meters, while the southern one is the lowest and with its 3879 meters it approaches the height of Little Ararat. The southern peak is easily accessible from Lake Kari without any equipment, on the other hand, the ascent to the northern one is difficult - a very steep scree slope, on which it is recommended to have enough experience with similar ascents and also enough time - the way to the summit requires first climbing the saddle between the southern and the western peak, descent into the crater, ascent to the saddle between the northern and eastern, traverse along the rubble slope of the northern and only then the actual ascent to the summit. Same back.

Lake Kari lies directly below the southern peak of Aragatsu at an altitude of 3190 m. The area around the lake is dominated by a large meteorological complex. It was built during the time of the Soviet Union, today only ruins remain. Only the hotel building with the restaurant is used, and the weather station itself has relocated to a modest little house on the other side of the lake.

Here and there on the slopes of Aragatsu you can see herding tents of nomadic natives. But one cannot get very close to the tents, which is the fault of erratic herding dogs.

We set up our base camp behind the lake – as in all of Armenia, everyone doesn't care where an adventurer builds his humble abode, so no one disturbed us during our overnight stay. That is, no one except for a group of Poles who didn't want to sleep and made noise late into the night.

Except for the tired Křemílk, we all went on an acclimatization hike to the southern peak of Aragatsu. We walked lightly, but even so, we were out of breath enough due to the elevation gain of almost six hundred meters. On the way, we met a group of English-speaking Armenians, dressed up for Sunday mass - the groomsmen wore long pants and patent leather jackets, a jacket casually thrown over the shoulder, the girls wore large sunglasses and jeans or dresses.

"That's not quite the right outfit for a mountain hike, is it?" we said softly. "They have to, they are Armenians," the girls explained to us, and it was clear that they also found their friends' clothes and shoes funny.

Fact window: You'd be hard-pressed to find an Armenian over the age of 12 wearing anything other than long pants. It's like the old days - a boy only fully matures when he puts on long trousers and patent leather shoes. It is a matter of Armenian honor.

The Armenians continued to discuss with us, but then they stayed on one of the snowfields we were crossing, rolled together for a while, and then set off on their way back. Our expedition continued towards the southern peak to an altitude of 3879 meters. The view from the top of Armenia's highest mountain was breathtaking – in the south, it was possible to see the cones of the great and small Ararat disappearing in the haze, far to the northeast of the foothills of the Caucasus. Beneath us, the Aragatsu Crater opened up, held by its four peaks. At this height, the wind was already quite cold, so we just took a quick photo, grabbed a summit cookie and headed back to the lake.

On our return, the sun was already setting, so we still managed to cook dinner and were about to get into our tents when a couple of guys passed by and invited us to the local weather station for tea. We accepted the invitation and in the evening we knocked on the door at the station.

"Barevdzes," we greeted the station crew, sat down around the table, where broken lavash was already prepared, brandy in bottles, and to keep their word, they made us the promised tea. The crew consisted of several young Armenians who managed to communicate in English, and one older commander who could not speak English. But it certainly wasn't a problem for the commander, he squeezed out of us all the Russian-Slovak-Czech words that he also knew, and despite minor obstacles we finally understood each other.

"Have some vodka," the commander urged us. "I made this myself. It's delicious. Take the lavash too." The vodka was really good, although the mulberry from Garni didn't even reach the ankles. "So you're from Czechoslovakia?" asked one of the younger meteorologists. "I was there. Prague, Brno, Ostrava," he started listing the cities to confirm that he knows our homeland well. Meanwhile, another Armenian was urged by his friends to take out his guitar. "Do you know Armenian folk music?" asked the commander. "We know, we heard the radio." "Oh, those are the modern ones, that's wrong. We'll play you traditional songs," he declared and advised the guitarist which one to play. The guitarist reached for the strings and it was immediately obvious that he was no amateur. He played one or two poignant songs that oozed sadness. The commander threw himself into singing positions, in which he had nothing to do, but he made up for it with his enthusiasm. Fortunately, he didn't interrupt the singing guitarist. The guitarist got another idea and strummed the strings again. This time, after the first few notes, everyone had to recognize the opening melody from the movie Desperado. The guitarist was certainly no stranger to flamenco rhythms, and the song was followed by a big round of applause. "Here, Cuba plays the guitar too!" exclaimed Křemílek in euphoria, pointing at me. I hoped it wouldn't come to that, because the Armenian guitarist was several classes better than me, but I picked up the guitar as part of the education. I played two songs by Jarek Nohavica, with which I showed the peak of my guitar skills, and handed the instrument back to its owner. "You play well," praised the guitarist. I scouted. "Well, I actually teach myself," the guitarist smiled. He played a few more songs and then we just talked. Before midnight we went for a walk. Even at this altitude, no more layers than underwear and a t-shirt were necessary.

The morning of the second day on Aragatsu was spent resting, after lunch we took a short walk past the lake and the abandoned research center buildings towards the insignificant ridge running south. We were joined by Křemílek, who miraculously regained his lost condition at yesterday's tea. We were only a few kilometers from the base camp - we saw a big storm cloud over Aragats and were glad that we had summited the day before.

After returning, we sat down to dinner at a restaurant by the lake. The service was terrible, the offer minimal and overpriced.

"What kind of beer do you have?" we asked the lady who came to serve us after about half an hour. "Goat." That surprised us. "But only black. In a can." That almost put us off, but there was no other choice, so we got it. We ordered a classic - shashlik. However, Lucka and Ondra tried another Armenian specialty called hash - stew made from sheep's leg, which was also recommended to us by the young Armenians from the previous day. It took nearly an hour to get our food, and it wasn't great. The shashlik was still edible, but the hash was the kind of smelly liquid that stuck out to drive sheep. In addition, the waitress brought a bunch of garlic. Although we tried to suppress the sheep's smell with it, it was rather worse with the increasing amount of garlic. The black Velkopopovicky goat in a can didn't really improve our appetite, so we preferred to arrive at the camp with our own food.

On the third day, the plan was to conquer the northern, highest peak of Aragatsu. This time, Ondra and Lucka stayed in the camp, while I, Bojínek and Křemílk, set off for turkey hunting. But the entire massif was shrouded in fog, which certainly showed no signs of receding. We scrambled up to the saddle between the small and large southern peak, but the fog was constant. In such weather, there was no point in trying to climb the northern peak at all, so we at least visited the large southern one again, where Křemílek had not yet been. Nothing at all could be seen, not even the bottom of the crater, and there was a gloomy misty silence over the place.

After a piece of chocolate, we started the descent. Ondra and Lucka hadn't even gotten up yet, it was very early. We crawled into our sleeping bags for a while, but in a few hours we had breakfast and were getting ready to leave Aragatsu. We tried to arrange with marshrutka drivers to take us to Ashtarak, but they were either expensive or full. Or they didn't talk to us at all. Some taxi drivers also wanted to take us, but at a rather unacceptable price. Finally, an empty minibus picked us up and dropped us for free on the main road below Aragats. Here we caught the trail without any problems and in two cars drove to Ashtarak.

Unfortunately for us, the marshrutkas didn't go to Gyumri on Saturday and we didn't want to sleep in Ashtarak again. Finally we arranged a taxi for 10000 drams. Surprisingly, six of us fit into one Golf – the taxi driver piled our five backpacks into the trunk, left it open and took a piece of string with him in the car to be safe in case the trunk lid needed to be tied. I sat in the front, the rest of the party squeezed into the back seats. The journey to Gyumri meant about a hundred kilometers along the main road constantly at the foot of the Aragatsu massif. The journey went by quickly, from time to time the taxi driver closed the tinted windows so that the policemen could not see how many of us were in the car. He dropped us off in Gyumri in the early evening and our only problem that day was finding accommodation.

Fact window: Gyumri, formerly Kumayri, Alexandropol or Leninakan, is the capital of over 200,000 in the northwestern province of Shirak. Between 1926 and 1988, the city was hit by large-scale earthquakes, reaching up to 7.2 degrees on the Richter scale. New construction has been taking place in the city mainly in recent years. The city is also known for the alleged apparition of Jesus on September 15, 2007, who was supposed to take the form of a luminous outline of a crucified figure - there is even a record of this phenomenon:

Originally, we wanted to go to Georgia that day, but there were no buses or marshrutkas. Again, the whole gang of taxi drivers persuaded us, but they offered a ride again for outrageously high amounts. We were already tired from traveling on the roads all day, so we decided to find some sleep. We finally managed to arrange an overnight stay at the Berlin Hospital & Art Hotel, where they let travelers sleep in their own tent in the backyard, while we paid the price of one room. We were even able to use the shower and the receptionist found out that the bus leaves for Borjomi in Georgia at 10:00 in the morning. We went to one of the night clubs for dinner - again we ran into a problem with the service, they didn't bring us several dishes, but they kept us paying for them. The local Gyumri beer was good, but warm.

In the morning, as expected, there was no bus, so we got two taxis to take us across the border to Georgia. Compared to the 30,000 drams offered yesterday, we got half the price, but again we only agreed on the town of Achakalki, from where we had to take a marshrutka to Borjomi.

INFO: The author runs the KGMK website. More photos in the Armenia and Georgia gallery.

Read about another Armenian peak: Azhdahak (3597 m)

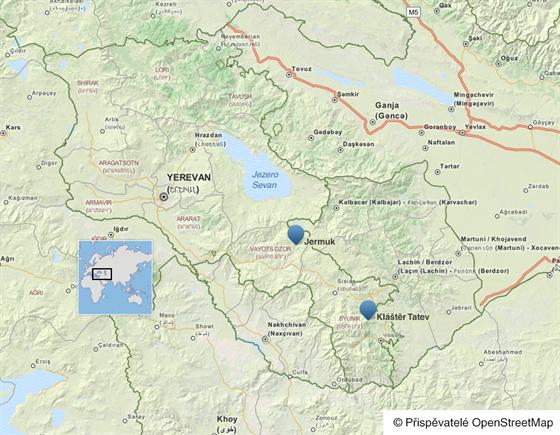

Show the place Mountains - hory - skaly - rocks on a larger map

Tags:

Tags: Prev

Prev