Frank Frištenský: I have never seen my mother cheerful - Novinky.cz<

Frank Frištenský: I've never seen my mother happy

It was clear from my father's side. It was Gustav Frištenský, a famous wrestler and his brothers. There was only a brother from his mother's. However, Frank Frištenský did not give up. He found out that his mother, Hana Kleinová, had lived in the Terezín ghetto for three years. Only she and her brother Petr survived the Second World War and the Holocaust from a large family. They never talked about their trauma.

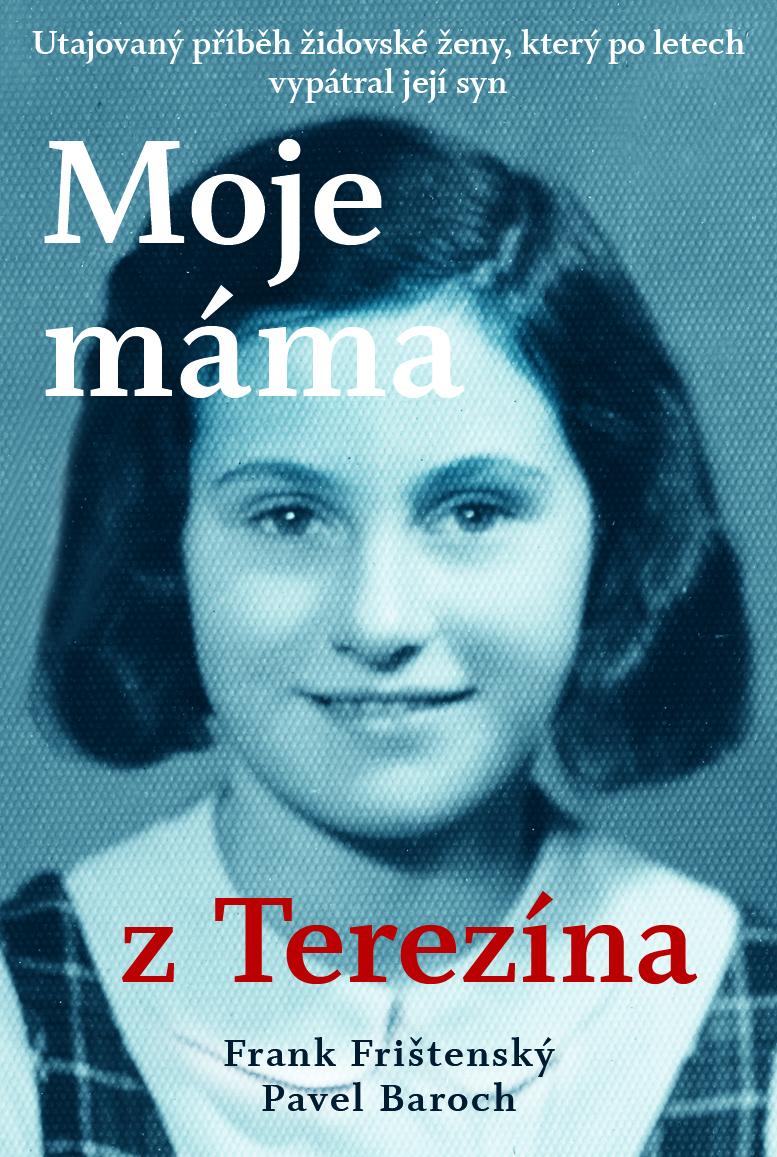

Frank wrote a book, My Mom from Terezín, about his mother and her difficult life. The literary form was given to her by the publicist Pavel Baroch. The book will be published by the Wall Publishing House with the support of the Endowment Fund for Holocaust Victims. It will be published on December 1 on the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the founding of the Terezín ghetto.

Your mother came to Terezín at the age of fourteen and spent three years there. Didn't you know that as a child?

Mom didn't talk about it at all. She never talked about Judaism, about what had happened to her parents, her family, herself, her friends. It was a huge trauma for her. She lived with it for the rest of her life, hiding it in her stomach. She was often sad.

Her brother Petr, who was transferred from Terezín to Auschwitz, then to another camp and then further west, to Germany, also survived. The train they were on was bombed. Many people died, but many also fled. Peter is among them. The two of them were the only ones who survived the whole family.

Having that out of it, I understand that everything she went through must have been a huge trauma for her mother that she couldn't talk about.

How do you explain that?

I think there are two groups of people. When I came to America in 1976, I lived with Arnošt Lustig's family for some time. He talked about the Holocaust, and his children Eva and Pepi knew exactly what had happened, they knew about their family. It wasn't with us.

So I call one group Arnoštová. These are people who talk about what they've been through because they think the next generation needs to know. Mom didn't think that way. And so there are those in the second group who didn't talk about it.

What made you look for your mother's story?

When I started telling my life story to friends, especially in America, they said I had to write it and that it could be a movie. I started and found that I only knew about my mom since she became my mom. But what was before?

When I was little and asked why I didn't have second grandparents, she said they had died before the war. And aunts and uncles? They all died before the war. She never said more.

It wasn't until Arnošt Lustig told me that my mother was Jewish. I didn't know what that meant, but I knew that as a child my parents and I went to Zábřeh in Moravia. Our friends became friends with the Taussigs, and Pavel Taussig and I say we are cousins.

It wasn't until I was very old that I found out that Pavel's parents had taken care of my mother when she returned from Terezín. Rudolf Taussig, Paul's father, was already dead, but Alice, his mother, knew a lot. And so she told me. There I first learned about Terezín and the fact that my mother's whole family left the chimney, so to speak.

How was your mother's family?

Bonded, she did a lot of things together. I think my dad was the most important thing to my mom. She is with him in a lot of photos and she wrote to one: Here is my dear dad. When he and Petr returned to Prague after the war, they did not know what had happened to their family and hoped that he would return. They waited several months. In vain.

Who else did you talk to about your mother besides Mrs. Taussig?

I interviewed the ladies who knew my mother, they were with her in Terezín. They were ninety years old and still called themselves girls. That was very nice. When they told me, it was like being with my mom. Some of them lived with her in the same quarters, they had the same job in agriculture, in the Terezín gardens.

The daily routine was more or less the same. However, they lived in permanent fear. They didn't know what would happen tomorrow. Every day they threatened transport, suffered from hunger, disease and cold. When you fight for your life every day for three years, it has to mark you.

Was my mother in Terezín until the end of the war?

Yes, it was luck. But she was selected for transport to Auschwitz. However, it was advertised. That has worked sometimes. But unfortunately someone else was cast instead. The numbers had to fit.

At first, the Germans enrolled the whole family in transports. And Rudolf Klein, his mother's father, once or twice told his family. Then the whole families were no longer treated and the mother was to go with her father. But her mother wrote herself instead. That saved her life. She asked Hilda Taussig Sweet, with whom she worked in one of Terezín's kitchens, that if they did not return, she would take care of her mother.

Your mother was probably a very strong woman because she thought she would protect you by not telling you anything about her trauma.

Yes. Even those I spoke to confirmed it to me. They wanted to protect their neighbors. They defended their children from the so-called second-generation syndrome. But it also has to do with the fact that I have never seen a happy mother.

Your life is colorful. You first emigrated with your parents to Switzerland, then you to America, where you started a sport.

I probably didn't even have a choice with my sports family on my dad's side. But I have always enjoyed sports.

Did you do well?

When I came to America, I was not even thirty and I did what I dreamed of. I taught physical education, I trained in women's volleyball. I thought there could be nothing better. My grandfather František, the youngest brother of Gustav Frištenský, has been to the wrestling tour twice in America. He did very well there, making good money.

When I was about fifteen, in Masečín, where they lived at the time, he told me: If you want to prove anything in life, you have to go to America. And when I stayed in America in 1978, I said, Grandpa, you can hear me, so here I am. America was a dream come true for me.

Now you live in the Czech Republic with your wife, who is American. But your children are in America. Why did you decide to do so?

I always felt like a Czech. I'll tell you a nice story. Pepi Lustig once took me and my brother to Jiří Voskovec in California. He told us about his grandmother, who was on a train to Russia during the reign of the emperor. She was sitting in the compartment with such a great gentleman who slept.

Then they stopped somewhere, it was late in the evening, the lord reportedly got up and said: Ma'am, aren't you hungry? I'm going to buy something. She said no and he brought a big steak. Then he introduced himself as Gustav Frištenský and going to wrestling tournaments.

Grandma later told Voskovec and he told her: Grandma, you're so stupid, why didn't you care anymore, I could be the famous Frištenský, not stupid Voskovec.

And when he told us, I realized that even after so many years of life, he speaks Czech so beautifully elsewhere! His Czech was excellent.

You also speak great.

It kicked me so hard at the time that I thought I must not forget and distort Czech. My youngest brother was ten years old when we left for Switzerland. There he speaks German at school and Swiss on the street. This makes a little goulash. The little brother once said something to his mother and she tells him: This is prostitution of speech. Either speak German or Czech with me. But don't mix it.

When my first daughter was born in 1984, my parents didn't speak English, and I thought I wouldn't speak German with her in America to talk to them. She was their first granddaughter. After her birth, I welcomed her in Czech. I have three children and they all speak Czech. They even scold me sometimes when I happen to speak English to them.

| It can come in handy at Zboží.cz: |

Tags:

Tags: Prev

Prev