iRadio Infection with brief contact, reinfection, questions about vaccines. What new variants of coronavirus can do<

The covid-19 virus in several parts of the world has independently mutated to higher infectivity and other features that complicate pandemic management. What do we know about the new variants, how they are spreading and what their introduction means for the coming months?

DataPraha / BrnoShare on LinkedInShare on FacebookShare on TwitterShare on Google+

At least two dozen people in the Czech Republic have already been confirmed by laboratories with the so-called South African variant of coronavirus, which spreads faster and overcomes immunity from covid or vaccination more easily.

One outbreak is reported by Brno, the other by Liberec. During the winter, the British variant has prevailed over the original virus line in the Czech Republic, and is now spilling over into Moravia. It is also more contagious and probably causes a more serious course of the disease.

How much more common are the new variants, infectious, deadly and more resistant to vaccines? And what exactly does that mean for the coming months and years of fighting the pandemic?

The spread of the three major coronavirus variants SARS-CoV-2 is monitored by the World Health Organization (WHO). In the first week of March, according to her data, the presence of the British variant was reported in 106 countries, the South African variant in 56 and the Brazilian variant in 29 countries.

Every second adds a mutation

The genome of the SARS-CoV-2 virus consists of about 30,000 nucleotides encoding genetic information (virus scheme). As the virus multiplies in infected bodies, any of these "letters" may accidentally change into others - mutating.

This should theoretically not happen as often as with some other viruses. In practice, however, the rapid spread of covid contributed to the large number of mutations and entire variants: the more patients, the more mutations.

Confirmed by Czech researchers: The new antibody works against all major coronavirus mutations

Read the article

"RNA viruses generally mutate very fast, but coronaviruses have corrective mechanisms, so they mutate a little slower than others," Jan Pačes from the Institute of Molecular Genetics of the Academy of Sciences explained to Radiožurnál.

"The mutation rate is about 25 per year (the number indicates the average number of mutations in one virus variant, ed. Note). For example, the seasonal flu or HIV virus mutates faster. Of course, there are many mutations in each person, and on average, every other person adds one mutation to the entire pool (virus gene pool, editor's note). Of course, when over 120 million people have become infected, there are a lot of mutations, "adds Pačes.

For comparison: the flu mutates about twice as fast, the HIV virus four times.

Most mutations are harmless and the altered virus fits. However, some mutations or combinations of mutations will change its key properties, such as increasing infectivity.

Despite the more contagious mutation, South Africa was able to slash the epidemic. The 'mysteriously' rapid decline raises questions

Read the article

If such a variant succeeds in competing with others, it will get, in addition to the code designation used by scientists and epidemiologists, a more catchy name used by the media. B.1.1.7 thus became the British variant (outside Great Britain), the Kentish variant (in Great Britain) or the familiar Brigita. Also, the changed virus may have more official designations, the South African variant scientists designate B.1.351 or 501Y.V2, the Brazilian variant B.1.1.28.1 and P.1.

In the Czech Republic, in the autumn, ie before the arrival of Brigita, variant B.1.258 dominated. Last year, it was represented by about half in the examined samples, with the critical situation in the Trutnov region in January this year it was 40 percent. To this day, it is probably the second most common option in the Czech Republic.

Although it is more contagious than the original line of the virus and it would make sense to name it, it has not received a media nickname. According to the customs, when variants of the virus are given names according to the place where they were first sequenced, paradoxically, it would not be a Czech variant, but a Slovak variant.

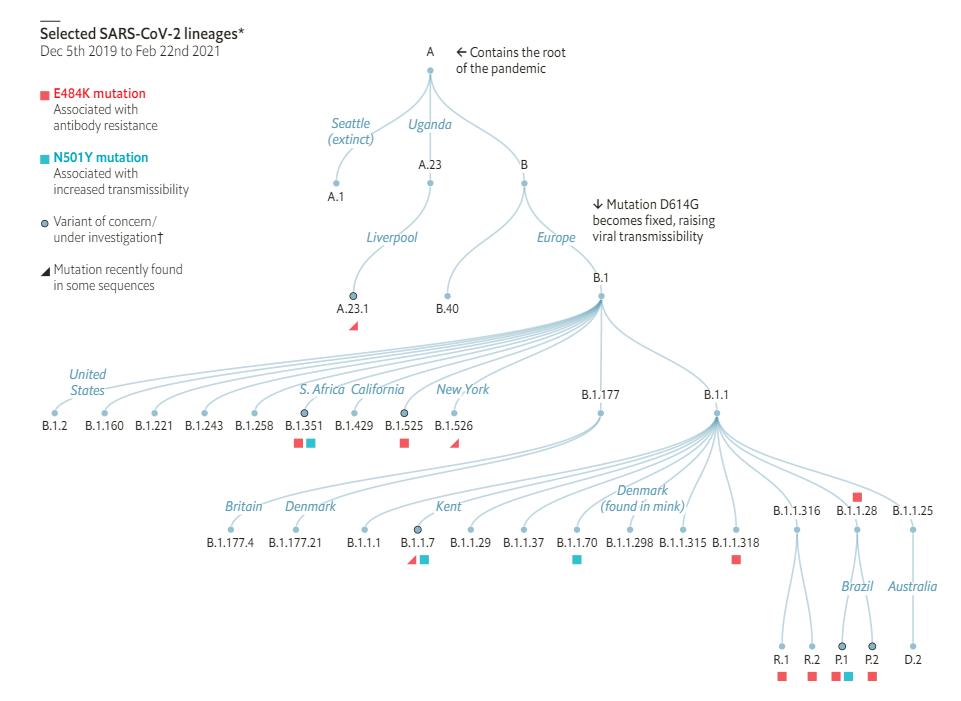

SARS-CoV-2 virus genetic lines

At the end of February 2021, The Economist described the global variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, their lines, and the problematic mutations (box below the box). The original Wuhan variant at the root of the "pedigree" is called A. The offspring are derived by adding a number or changing the letter if the mutation is more substantial. The variant that prevailed in Europe is thus called B.1, its most well-known variant in one generation B.1.1.7. The diagram also shows the "Czech-Slovak" variant B.1.258 or the Seattle variant A.1, the spread of which was stopped.

Widespread nicknames such as British, South African or Brazilian usually obtain variants according to the location of the laboratory where they were identified. The WHO does not recommend such names, it suggests that the names of diseases should be based, for example, on their manifestations. Geographical names can have a number of negative side effects - for example, they can be an argument of governments against the support of laboratories that could monitor the virus. The stigma of the "Chinese virus" is probably one of the reasons why the Chinese government has not shared much of its variants.

However, the Czech-Slovak variant failed in the genetic battle.

"The British variant has one change that helps the virus attach better (on a human cell, ed. Note)," Pačes warned in mid-February. "It has been shown experimentally to spread faster and easier."

In practice, this means that a person can become infected during brief contact with the infected person. "It takes about two to three months to push out the other variants. Not completely, but it prevails. "

Some mutations occurred independently of several coronavirus variants. Typically those that increase its infectivity or resilience. These mutations favor the virus over competitors, so whenever they appear, they tend to gain ground.

Like a nightmare. More aggressive mutations and a lack of measures have made Brazil an open-air laboratory

Read the article

At the same time, the higher infectivity of the virus is in some respects more serious news than higher mortality. Thus, pandemics will overwhelm hospitals faster, and at the same time stricter restrictions on social life and higher vaccination coverage are needed to manage it. About 70 percent of the population vaccinated in the original version of coronavirus was typically reported outside the collective immune system. Not so much may be enough.

Individual mutations also have names, only media nicknames have not been received yet. Known - and dangerous - is the E484K, which appeared in both the South African and Brazilian and now also in the British variant.

That's pretty bad news. This mutation is located on the so-called spike protein, which binds to the ACE2 receptor, typically in the lungs as well as other organs. It is this protein that most vaccines "teach" the human immune system, and the E484K mutation therefore reduces their effectiveness. The extent to which this happens with individual vaccines and what this practically means to manage a pandemic is still the subject of research.

Epidemiologist Eric Feigl-Ding of Harvard University presents one of the first large-scale studies on this topic in a Twitter thread. In several graphs, it summarizes how the most widespread variants - British without E484K mutation, South African and Brazilian with it - respond to Pfizer and Moderna vaccines.

How do the variants differ?

The global distribution of the most important variants, their mutations and changes in key features of the virus are monitored by the WHO. A quick overview of the findings so far can be found in its table.

Detailed comparisons - including references to the studies he draws from - can be found in the WHO Weekly Summary as of February 23 (in English). Data on infectivity, mortality and other characteristics are always quantified in relation to other variants of the virus; for example, the British variant is 36 to 75 percent more contagious than the "nameless" SARS-CoV-2.

The Czechia fell asleep

Researchers were able to react quickly to the spread of covid early last year, map the genetic information of the virus and synthesize vaccines in record time. However, with the growing number of mutations, there is a risk that they will lose the lead. Therefore, since the beginning of the year, the WHO has been calling on member countries to monitor mutations.

"With the advent of vaccination and the onset of resistance of the population to those existing variants of the virus, others may emerge that escape the immune system," emphasizes Michal Kolář from the Department of Genomics and Bioinformatics at the Institute of Molecular Genetics of the Academy of Sciences.

"It simply came to our notice then. Detect difficult patients' viruses as well as viruses that have infected vaccinated people. It can be very important to isolate such variants. Because otherwise what vaccination may be wasted, Professor Václav Hořejší probably rightly calls uncontrolled immunization. Suddenly we would be at the beginning again, "Kolář points out.

Since last October, regular monitoring has been carried out by the British, who sequence genetic information - ie read it - on about a third of those who test positive. The "reward" for their diligence was naming the variant of the virus they described first.

Source: Public Health England, Investigation of amendments SARS-CoV-2 variantThe Czechia has not yet started systematically monitoring the options. The aforementioned Institute of Molecular Genetics is dedicated to it on its own initiative, but scientists lack official support.

"The goal now is to sequence about one percent of viruses in positive patients per week," explains Kolář. "If the Czechia has about 100,000 new positive patients a week, then that means a thousand samples that we would like to analyze every week. Capacity is here. As I saw the last promises, the laboratories in the Czech Republic are able to sequence 900 to 1300 samples. "

"To understand what's going on, we have to do this for weeks," he continues. "It simply doesn't make sense with a few thousand samples. The Czechia has fallen asleep in this regard. We could have had sequences much earlier. There were even initiatives from other laboratories before the summer of 2020. We could already have better information. "

Therefore, they are creating a database of sequenced samples collected from Czech laboratories last year at the Institute of Molecular Genetics. So far, it contains about a thousand anonymized records from the entire course of the pandemic.

The results should be taken with caution: the selection of samples for sequencing has so far been random and may be influenced, for example, by monitoring local outbreaks in more detail.

If we select only the months in which the laboratories analyzed at least a hundred samples, the expected picture is outlined. During 2020, the original European variant B.1 was gradually replaced by the "Czech-Slovak" B.1.258. At the beginning of this year, it also gave way to the British line B.1.1.7.

A similar picture is offered by a simple "pedigree" of the virus from data from Czech laboratories. The first part shows how "parents" through mutations became "descendants", ie how, for example, the European variant B.1 through B.1.1 evolved into the British B.1.1.7. The size of the wheel indicates how many samples the Czech laboratory has detected. As a result, it is clear, among other things, that the middle generation of this line, B.1.1, was significantly less successful than the parent B.1 and the descendant B.1.1.7. The second part of the graph then shows in which months the variant appeared regularly.

"Variant B.1 is old, the others that start with B.1 have been branched out of it, today it should no longer occur here," comments the graph of molecular geneticist Pačes.

"However, it is possible that you will find it in the data today," he adds. "It can be either a designation for a hitherto unknown line or a worse sequencing depth. It is also possible that the patient was infected with two different strains - so it is not clear which mutation he has. Or it may be a collection from a long-term patient in whom many minor mutations have accumulated. So I would be careful with the interpretation. "

Data from Czech geneticists can also be found on the websites of international agencies that monitor the spread of mutations: the European Center for Disease Spread and Control and the global GISAID initiative. These make it possible to monitor the spread of variants and mutations across the planet.

"Financing is still a completely unresolved issue," adds Jan Pačes. "Sequencing is not easy. We have enough devices in the Czech Republic, that is not a problem. We also have enough people who will do it more or less voluntarily for at least some time. We can start with that initiative, but we no longer have the money to do it for the state, the state should solve it. He also has to say how many sequences he wants per week. We propose a thousand. Maybe he'll want 10,000 or just a hundred. That depends on the state. "

During March, the initiative was taken by the State Institute of Public Health, which began coordinating laboratories and publishing the results of sequencing. However, it does not solve the problem of financing.

We need more types of vaccines

Monitoring of covid mutations alone is not enough; vaccines must also be adapted accordingly. The European Medicines Agency is therefore now looking at a way to speed up the approval process for vaccines that have resulted from modifications to those previously approved - especially possible modifications to Pfizer, Moderna and AstraZeneca vaccines.

"Some vaccines against viral diseases remain effective for many years after their development and provide long-term protection, such as measles or rubella vaccines," said Klára Brunclíková, a spokeswoman for the State Institute for Drug Control. "On the other hand, in diseases such as the flu, the composition of the vaccine must be changed every year to be effective. Because the virus mutates. "

Covid-19 is unfortunately the second case.

Jan Boček, Štěpán Sedláček, Kristína ZákopčanováShare on LinkedInShare on FacebookShare on TwitterShare on Google+

Tags:

Tags: Prev

Prev